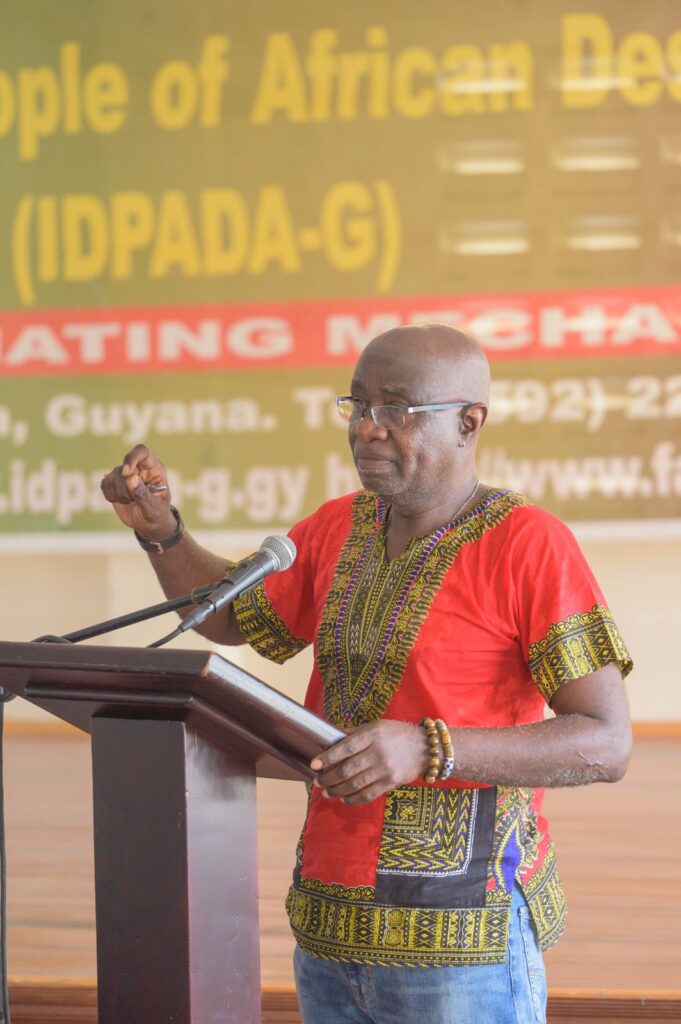

Dr. Wazir Mohamed’s Presentation to Lands Commission of Inquiry- Part I

The concern about land ownership continues amidst growing perception the People’s Progressive Party /Civic government is moving to dispossess Africans and Amerindians from wealth accrued through ancestral land rights by their land distribution programme. Village Voice News will be examining this issue from the perspective of difference voices.

Today we feature Part I of a presentation made by Dr. Wazir Mohamed to the Lands Commission of Inquiry on November 23, 2017. Dr. Mohamed, who is Guyanese, is an Associate Professor, Sociology, Indiana University East, USA

Introduction

Honourable Commissioners,

I am especially pleased to be given this opportunity to speak with you, and to share my knowledge on the history of the land problem of Guyana. In this presentation I begin by outlining some salient facts about the history of the struggle by the salt of the earth, the laboring population for access to land from the early 19 century.

I prefer to speak about the 19th century, as the period of the sugar revolution. This is necessary because acquisitions of lands outside of the European sugar plantations, were connected and integrally related to the needs of the sugar industry. The sugar barons, through their influence over the colonial state, exercised absolute controls over access to land, especially Crown Lands between 1838 and 1898. Planter influence and control over access to land was not limited to Crown Lands.

They had unlimited and in many instances, what can reasonably be described as unfettered controls over the development of land policy. Land policy was a primary tool used after emancipation to control movement and price of labor. A reading of the land ordinances of 1835/36, 1839, 1851, 1852, 1856, 1857, 1861, and 1898 render an understanding of the history through which our current land tenure structure evolved. Closer reading of these ordinances demonstrates the following:

- The ordinances of 1835/36, 1839, and 1861 – virtually prevents the former enslaved to acquire Crown

- The ordinances of 1851, 1852, 1856, and 1857 – produced fragmentation in the villages, and in many ways created bottle-necks, which thwarted the original intent of the former enslaved to work the backlands of the villages as cooperatives.

- The ordinance of 1898 – opened Crown Lands at very concessionary rates. Lands which for 60 years were out of reach of the former enslaved, became accessible to the formerly indentured, who were being hemorrhaged out of the sugar because of the global sugar crisis of the This lead to the evolution of the rice industry.

- The result – disparity in tenure between the two most populous sections of the laboring population.

Honourable Commissioners, we cannot make sense of the dilemma we face today with respect to the multitude of land disputes, and to lack of equity that permeate the society between different communities, and classes of our population without recourse to an understanding of the planter mentality – which informed colonial policy and hence law making.

The problems we face, the very reason for this commission’s existence, is deeply connected to the structure of land tenure developed in the period 1838-1898. In many respects the divergent access to land between descendants of the enslaved and descendants of indentured servants emerged, and evolved because of the needs of sugar. I have argued in other places that the structure of our ethnic/racial culture have its roots in the divergent access to land.

I arrived at this conclusion after years of studying this problem. I grew up in a farming household, and is familiar with farming in the East Indian as well as the neighboring African Village of Farm, East Bank Essequibo. The inequality in access to tenure I observed during my childhood between East Indians and Africans raised many unanswered questions. This lead me to study the roots of ethnic/racial problem.

Honourable commissioners, my journey to find answers to this troubling racialized structure of our history lead me to pursue studies towards the PhD. I have spent years looking through documents at the Guyana National Archives, at the British National Archives, and at the School of Oriental and African Studies – home of the Archives of the London Missionary Society. Because of my familiarity with that period of our history, I would argue that there is a lot more to discover with regards to the structure that evolved – which I would say without doubt was geared to keep the African Population Landless.

What began in the 1820s as a means of ensuring that all labor was available for plantation work, soon became a system that used control over land as the means of labor control. This later evolved to become a culture of control. Before I go on to give you some of the insights into the land policies as they evolved, permit me to encourage you not to make the same error of successive governments, in sweeping this history under the table. It would be highly regrettable if this commission were to leave these fundamental issues untouched and unresolved.

The answer to the dilemma that we face lies in the structure of our history. Let us briefly examine salient aspects of the history between the abolition of the slave trade in 1806 and the global sugar crisis of the 1880s. I call this period, the Sugar Revolution.

The Sugar Revolution and the labor/land market: 1806 and beyond

It is pertinent that I begin this section with a passage taken from Alan Younge’s, approaches to Local Self Government in British Guiana, published in 1958. Younge (1958:10) noted that,

“In British Guiana, where unoccupied land was available in vast quantities, land policy, private and official, was carefully shaped towards keeping the Negro landless. On the official side, measures were introduced to prevent both the illegal and the legitimate use of Crown Lands by the Negroes.”

Younge goes on to give details about the vagrancy laws, and other statutes through which the enslaved and former slaves were to be kept landless. Other scholars, namely Alvin Thompson (2002, 2006) and Emilia DaCosta (1994) gave as much details as available in the archives to show the extent to which planters and the colonial state went to prevent, destroy, and obliterate occupation of lands by runaway slaves.

Unlike other parts of the Americas, British Guiana was the only colony in the Caribbean where runaway communities were completely obliterated, and where the African population have been denied access to the lands occupied albeit illegally by their ancestors who were fighting freedom and independence from the hazards, and from physical and mental slavery of plantation life. I think it would be necessary for this commission to at least acknowledge this historical travesty.

Another historical travesty that should come under your consideration for acknowledgement were the roadblocks placed in the path of the enslaved to effectively use the right to cultivate garden plots and provision grounds as the law stipulated. The statute that outlined the requirement for provision ground allocation were not honored in the letter and spirit of the law. It was honored in the breach.

In the period immediately following the abolition of the slave trade, British Guiana found itself in dire straits, it had approximately 100,000 enslaved individuals, when its land endowment necessitated that it should have had more than 2 million. As a means of resolving this dilemma, the colonial enterprise opted for a one crop economy, cotton and coffee was jettisoned, plantations were consolidated, and all available labor were herded to meet the demands of the sugar industry.

Rather than diversify the economy, the planter class and the colonial office decided that sugar was to be the crop of choice. Against all odds, British Guiana opted for access to the global sugar market. The sugar economy required all hands-on deck. The colony of British Guiana became part of the global spiral, where production of single commodities was driven by increased regimentation of slave labour.

British Guiana joined other one crop colonies such as Mauritius and Cuba in a new global competition to produce sugar to fuel industrialisation, as Mercantile Capitalism was beginning to give way to the free market. In the same vein, the United States South became the primary producer of Cotton, and the Paraiba Valley in Brazil became the premier producer and supplier of coffee. British Guiana was not a blank slate, its history from thereon was being written, as its economy and internal arrangements were shaped to meet the demands of global competition for sugar. This is what I call the sugar revolution.

Honourable commissioners, everything that followed, was subject to the demands of global competition for sugar. This is why runaway communities were obliterated, and why garden plots and provision ground cultivation almost disappeared (Da Costa, 55). I make these points to lay the basis for you to understand the mindset within which post emancipation land policy was shaped. Post-emancipation land policies were interconnected to labor policy.

It is incumbent on this commission to delve into the complex interplay, in order to figure out the role labor policy played in the erection of land policy, and how these served to keep land away from the African population during the period of the sugar revolution. And consequently, the role land policy played in the rise of the rice industry, and hence the disparity that exist between Africans and East Indians with respect to land ownership and occupation.

To be continued….

Source: ResearchGate

Link to Original article

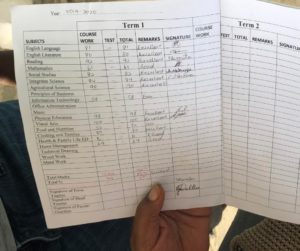

On March 19th 2020, members of the International Decade for People of African Descent Assembly-Guyana travelled to various villages in Region 5, Mahaica-Berbice, to lend support to the families of children affected by the March 6th protest in Bath Settlement. The protest, related to what was termed, ‘the delay in the release of the 2020 Election Results’, targeted a state owned school bus transporting students predominantly of African descent and resulted in five (5) of these students between the ages of 13-16, sustaining physical injuries to their heads and other parts of their bodies. The psychological trauma suffered by the students remains largely unknown. During the visit, household supplies were presented to the families and tablets were given to the students to aid the completion of their schoolwork from home.

On March 19th 2020, members of the International Decade for People of African Descent Assembly-Guyana travelled to various villages in Region 5, Mahaica-Berbice, to lend support to the families of children affected by the March 6th protest in Bath Settlement. The protest, related to what was termed, ‘the delay in the release of the 2020 Election Results’, targeted a state owned school bus transporting students predominantly of African descent and resulted in five (5) of these students between the ages of 13-16, sustaining physical injuries to their heads and other parts of their bodies. The psychological trauma suffered by the students remains largely unknown. During the visit, household supplies were presented to the families and tablets were given to the students to aid the completion of their schoolwork from home.